I’m not the most active person on LinkedIn, more of a quiet observer who scrolls now and then. I do make new connections occasionally (selectively, of course). At the risk of upsetting some people, LinkedIn can sometimes feel like a stage where many are more interested in “showing off” than sharing real insights or adding value.

One person I always make a point to follow is Denise Chisholm. Her insights are consistently outstanding, often making me pause, think, and challenge my own views. Here is another timely update from her.

Here is a section:

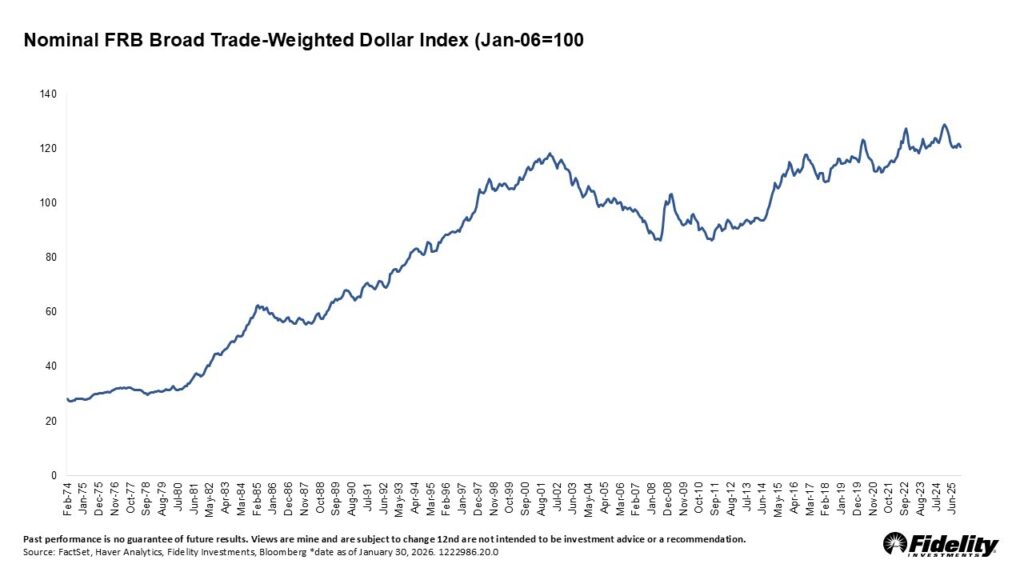

The dollar is back in the spotlight. After a sharp leg lower during April’s “tariff tantrum,” the dollar spent much of the summer moving sideways. Over the past week, however, weakness has begun to re‑accelerate and with it has come a familiar narrative: dollar debasement, the end of US exceptionalism, and warnings that currency weakness poses a direct threat to equity markets.

Rather than lean into the rhetoric, it is worth stepping back and asking a simpler question: what has dollar weakness actually meant for stocks historically? Over the past year, the dollar’s decline ranks in the bottom decile of historical moves, meaning the weakness has been notable relative to history. But in the context of the full dataset going back to the 1970s, the magnitude of depreciation remains fairly modest.

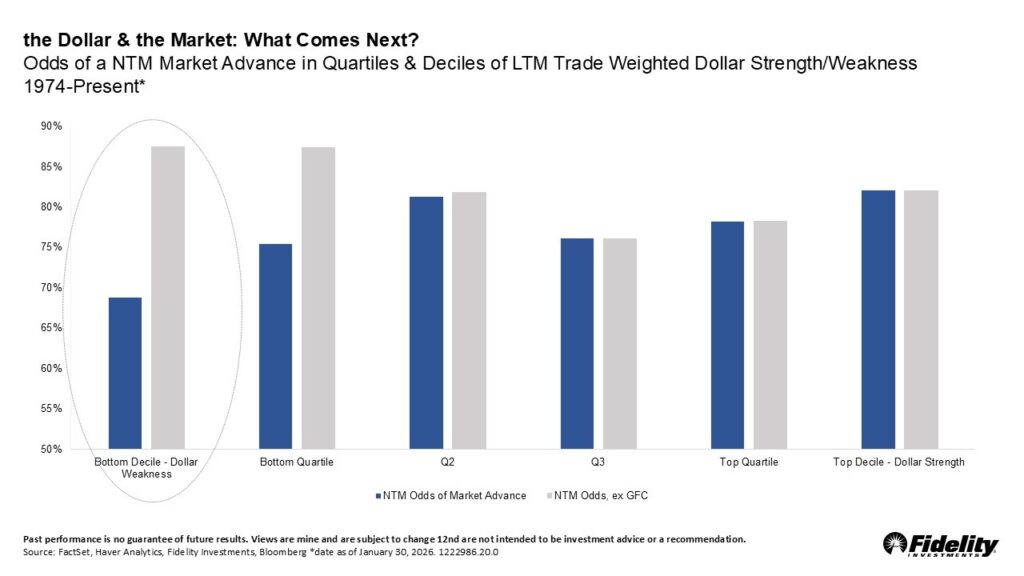

So what happened to equity markets following similar periods of dollar weakness? At first glance, the headline numbers are not especially encouraging. Historically, when the dollar has fallen into its weakest decile, stocks have still risen over the following year about 68% of the time – positive, but the lowest success rate across all buckets.

On the surface, that suggests dollar weakness can act as an overhang. But there is an important caveat. That weaker forward performance is heavily influenced by a single episode: the Global Financial Crisis, when dollar weakness coincided with a deep recession and a historic equity drawdown.

When you look just outside that period, the pattern flips. Excluding the crisis, episodes of extreme dollar weakness are associated with the highest odds of equity gains over the following year – nearly 90%. In other words, the apparent caution in the data is highly conditional. Historically, outcomes have depended far more on the economic backdrop than on the currency itself.